Special Topics

The Historical Development of Buddhist Vegetarianism

Practicing Vegetarianism to Cultivate Compassion

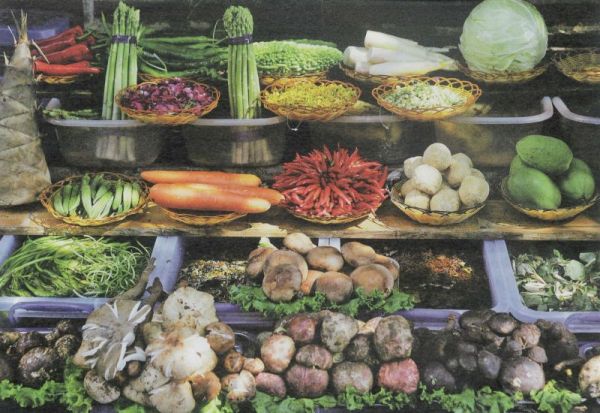

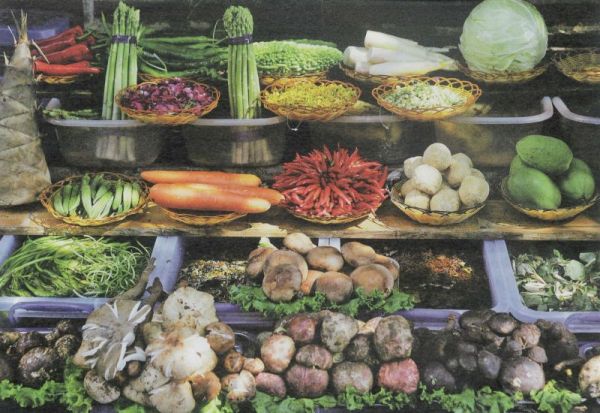

Vegetarianism is especially promoted in Chinese Buddhism. The principle is rooted in practicing the Buddhist precept of non-killing (ahiṃsa), which can help practitioners cultivate a compassionate mind. Nowadays, it has become a new trend to turn vegetarian or vegan for health purposes, as well as for the protection of animals and the environment. Vegetarianism may be a personal choice, but it certainly concerns the lives of other species in addition to the well-being of the earth's entire ecosystem.

Many people associate vegetarianism with Buddhism. It doesn't surprise a Han Chinese that a Buddhist monastic practices vegetarianism. So, do Buddhist monks have to become vegetarian? The historical development of the Buddhist diet suggests otherwise, in the early days of Buddhism. As Buddhism spread to other parts of the world, the Buddhist diet started to vary from place to place due to their respective cultures and customs. Unlike Chinese Buddhism, other Buddhist traditions such as Tibetan Buddhism, Theravada Buddhism, and Japanese Buddhism do not regard eating meat as a taboo. In fact, Chinese Buddhist monks didn't actually adopt vegetarianism until 500 years after Buddhism was introduced to China.

Many people associate vegetarianism with Buddhism. It doesn't surprise a Han Chinese that a Buddhist monastic practices vegetarianism. So, do Buddhist monks have to become vegetarian? The historical development of the Buddhist diet suggests otherwise, in the early days of Buddhism. As Buddhism spread to other parts of the world, the Buddhist diet started to vary from place to place due to their respective cultures and customs. Unlike Chinese Buddhism, other Buddhist traditions such as Tibetan Buddhism, Theravada Buddhism, and Japanese Buddhism do not regard eating meat as a taboo. In fact, Chinese Buddhist monks didn't actually adopt vegetarianism until 500 years after Buddhism was introduced to China.

Many people associate vegetarianism with Buddhism. It doesn't surprise a Han Chinese that a Buddhist monastic practices vegetarianism. So, do Buddhist monks have to become vegetarian? The historical development of the Buddhist diet suggests otherwise, in the early days of Buddhism. As Buddhism spread to other parts of the world, the Buddhist diet started to vary from place to place due to their respective cultures and customs. Unlike Chinese Buddhism, other Buddhist traditions such as Tibetan Buddhism, Theravada Buddhism, and Japanese Buddhism do not regard eating meat as a taboo. In fact, Chinese Buddhist monks didn't actually adopt vegetarianism until 500 years after Buddhism was introduced to China.

Many people associate vegetarianism with Buddhism. It doesn't surprise a Han Chinese that a Buddhist monastic practices vegetarianism. So, do Buddhist monks have to become vegetarian? The historical development of the Buddhist diet suggests otherwise, in the early days of Buddhism. As Buddhism spread to other parts of the world, the Buddhist diet started to vary from place to place due to their respective cultures and customs. Unlike Chinese Buddhism, other Buddhist traditions such as Tibetan Buddhism, Theravada Buddhism, and Japanese Buddhism do not regard eating meat as a taboo. In fact, Chinese Buddhist monks didn't actually adopt vegetarianism until 500 years after Buddhism was introduced to China.The Evolution of Buddhist Viewsof Diet

The Buddha founded the first Buddhist sangha in the fifth century BC. The land now called India had diverse faiths and religions, with various dietary habits. Though Buddhism stresses the principle of non-killing, the Buddha didn't forbid his disciples from eating meat, since the Buddha and the sangha must eat whatever people donated as alms. Except for the flesh from ten kinds of creatures, including elephants, horses, nagas, dogs, and humans, consuming the "three kinds of pure meat (tri-koṭi-śuddha-māṃsa)" was actually permitted. The latter refers to fish and animals that are not seen or heard when being killed, or suspected to have been purposely slaughtered for the eater.

According to epigraphic documents, a law in King Ashoka's time (the mid-third century BC) forbade its citizens from slaughtering animals during particular periods of time and in certain places. Even with the policy based on non-killing, the government didn't force everyone to go vegetarian. Nevertheless, the idea of vegetarianism for non-killing purposes has since been highly valued in Indian societies.

During the first few hundreds of years after Buddhism was introduced to China, although the emperors and citizens made offerings to the Three Jewels, they mainly offered the three kinds of pure meat. No monastic was prohibited from eating fish and meat by law or by Buddhist precepts, until Emperor Wu of Liang stipulated the law that required monastics to become vegetarians. Emperor Wu (reigning from 502 to 549 AD), whose given name was Xiao Yan, was a both a devoted Buddhist himself and a lifelong vegetarian. To put the faith into action, he wrote an article entitled "Abstention of Wine and Meat" based on the Mahaparinibbana Sutta and the Lankavatara Sutra, arguing that monastics must stop eating meat and keep a vegetarian diet. Under the strict rule and active promotion efforts of Emperor Wu, vegetarianism later became part of Chinese monastic life.

Through the Buddhist culture, vegetarianism has continued to this day and has become popular in society, as part of many people's daily lives.

According to epigraphic documents, a law in King Ashoka's time (the mid-third century BC) forbade its citizens from slaughtering animals during particular periods of time and in certain places. Even with the policy based on non-killing, the government didn't force everyone to go vegetarian. Nevertheless, the idea of vegetarianism for non-killing purposes has since been highly valued in Indian societies.

During the first few hundreds of years after Buddhism was introduced to China, although the emperors and citizens made offerings to the Three Jewels, they mainly offered the three kinds of pure meat. No monastic was prohibited from eating fish and meat by law or by Buddhist precepts, until Emperor Wu of Liang stipulated the law that required monastics to become vegetarians. Emperor Wu (reigning from 502 to 549 AD), whose given name was Xiao Yan, was a both a devoted Buddhist himself and a lifelong vegetarian. To put the faith into action, he wrote an article entitled "Abstention of Wine and Meat" based on the Mahaparinibbana Sutta and the Lankavatara Sutra, arguing that monastics must stop eating meat and keep a vegetarian diet. Under the strict rule and active promotion efforts of Emperor Wu, vegetarianism later became part of Chinese monastic life.

Through the Buddhist culture, vegetarianism has continued to this day and has become popular in society, as part of many people's daily lives.

Resource:

Issue 447 of Life Magazine, Dharma Drum Publishing Corporation

Text: Shi Yan-Xiao (釋演曉)

Translation: Hsiao Chen-An

Editing: Chang Chia-Cheng (張家誠), Keith Brown

Translation: Hsiao Chen-An

Editing: Chang Chia-Cheng (張家誠), Keith Brown

Extended Reading:

What Is the Buddhist View on Diet? by Master Sheng Yeng