Global Buddhist Community

The Chan Practice of Non-abiding (I)

This article is written by Ven. Guo Xing, a Dharma heir of the late Master Sheng Yen. Ven. Guo Xing is the Managing Director of DDM's Chan Hall and the former abbot of the Dharma Drum Retreat Center, New York, as well of the Chan Meditation Center in Queens, New York. The article was translated from Chinese by Echo Bonner and Harry Miller, and edited by Ernest Heau.

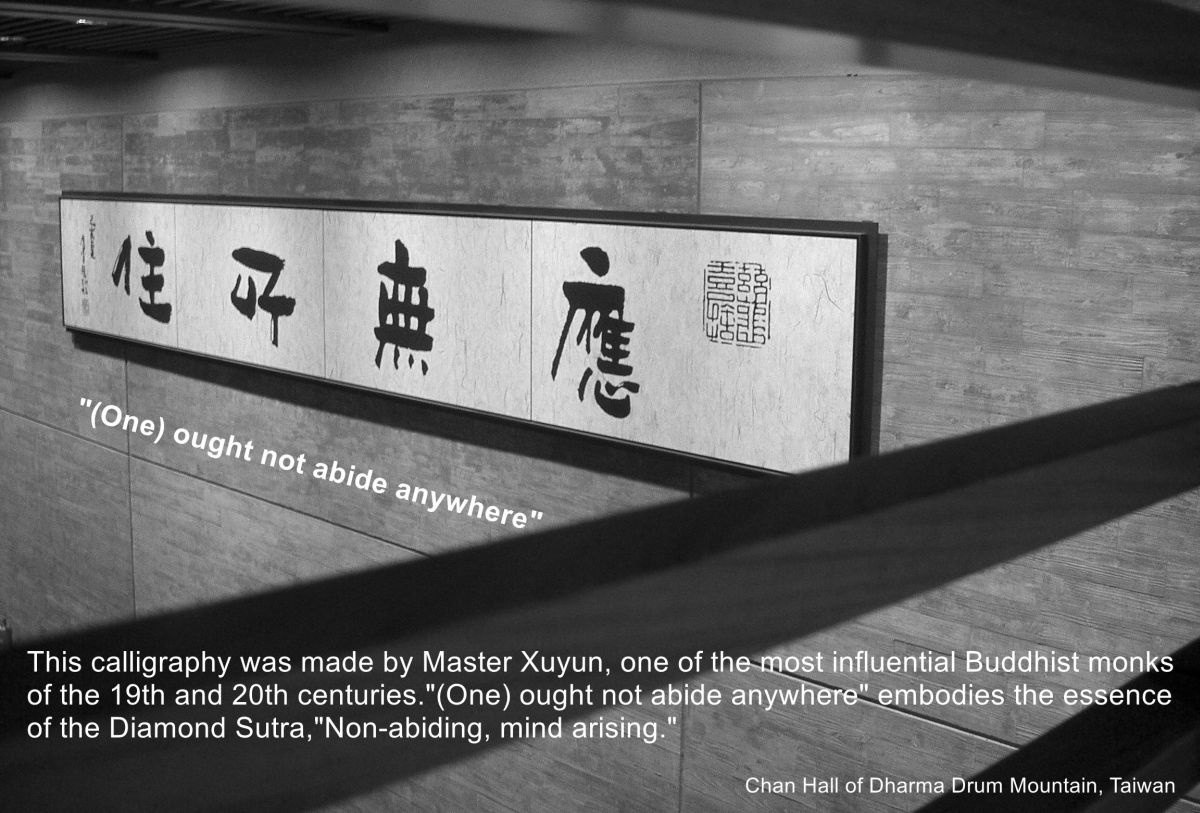

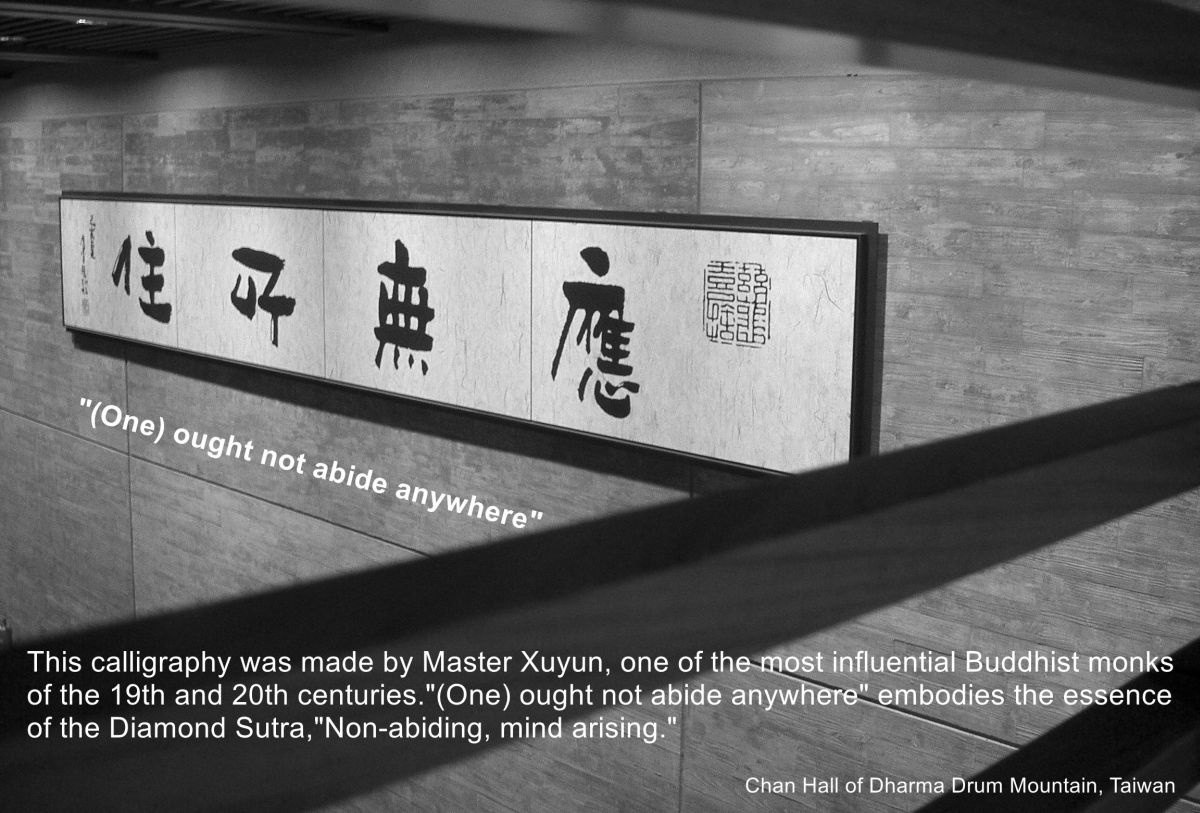

The Diamond Sutra contains the sentence, "(One) ought not abide anywhere, and there will arise this mind." Before he became the Sixth Patriarch, the young Huineng became enlightened when he heard this single sentence. In Chan, we often use a briefer phrase, "Non-abiding, mind arising." This phrase appears within the entrances to Nung Chan Monastery and the Chan Hall of Dharma Drum Mountain in Taiwan, as well as the Chan Hall of the Dharma Drum Retreat Center in the United States. Master Sheng Yen continually brought up this phrase during long retreats, explained the concepts behind it, and asked retreatants to practice accordingly.

The Diamond Sutra contains the sentence, "(One) ought not abide anywhere, and there will arise this mind." Before he became the Sixth Patriarch, the young Huineng became enlightened when he heard this single sentence. In Chan, we often use a briefer phrase, "Non-abiding, mind arising." This phrase appears within the entrances to Nung Chan Monastery and the Chan Hall of Dharma Drum Mountain in Taiwan, as well as the Chan Hall of the Dharma Drum Retreat Center in the United States. Master Sheng Yen continually brought up this phrase during long retreats, explained the concepts behind it, and asked retreatants to practice accordingly.

The Chan school places great importance on "non-abiding, mind arising" because the intrinsic nature of the mind is exactly non-abiding. If you wish to be enlightened, your actions must be in accordance with "non-abiding, mind arising." Not only must you have a clear sense of this idea, but your every action, word, and thought must be in line with it. This idea that all actions of body, speech, and mind should be in accord with the concept of non-abiding is expressed in the saying by the Huineng: "As the mouth speaks, so the mind acts."

There are many places in the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch that refer to how one should practice non-abiding. For example, the chapter "Samadhi and Wisdom Are One" says that those who practice non-abiding will see the emptiness inherent in virtue and evil, beauty and ugliness, enemy and friend, demeaning and argumentative language. Such a person does not engage in or think about reward or injury. Thought after thought, he or she doesn't engage in or think about the previous condition. If the previous thought, present thought and future thought continue without stopping, this is called "bondage." If, in regard to all dharmas, thought after thought continues with non-abiding, this is called "unbinding."

Obviously, on an intellectual level, at the outset one knows that all worldly ideas of virtue, evil, beauty and ugliness are empty, impermanent and without self. Our enemies as well as those close to us are empty, impermanent and without self. The deceptions and difficulties that others give to us through words and arguments are also empty, impermanent andwithout self. We should not be ready to seek revenge or argue and offer explanations. In applying this principle, when we are present in each moment, thought after thought, we do not react, make distinctions, or grasp or reject. However, when each successive thought is caught up with the previous thought and the present state (whatever your attention turns to) is encountered, then distinctions of other, self, right, wrong, good and bad, arise. This thought process then triggers the subsequent thought (which is now the present thought). And then the next thought will follow this present thought, and we again make distinctions between other, self, right, wrong, good and bad. This thought process continueswithout end. Again, this is bondage. If the mind doesn't differentiate, grasp or reject any past, present or future phenomena, then this is called "without bondage."

Obviously, on an intellectual level, at the outset one knows that all worldly ideas of virtue, evil, beauty and ugliness are empty, impermanent and without self. Our enemies as well as those close to us are empty, impermanent and without self. The deceptions and difficulties that others give to us through words and arguments are also empty, impermanent andwithout self. We should not be ready to seek revenge or argue and offer explanations. In applying this principle, when we are present in each moment, thought after thought, we do not react, make distinctions, or grasp or reject. However, when each successive thought is caught up with the previous thought and the present state (whatever your attention turns to) is encountered, then distinctions of other, self, right, wrong, good and bad, arise. This thought process then triggers the subsequent thought (which is now the present thought). And then the next thought will follow this present thought, and we again make distinctions between other, self, right, wrong, good and bad. This thought process continueswithout end. Again, this is bondage. If the mind doesn't differentiate, grasp or reject any past, present or future phenomena, then this is called "without bondage."

How then do we not differentiate, grasp or reject phenomena of the past, present and future? We need to cultivate samatha (samadhi) and vipassana (contemplation), or, if one practices Chan, Silent Illumination or Huatou. These contemplation methods lead to the state of non-differentiation—neither grasping nor rejecting past, present or future phenomena. However, the mind can only achieve this effect when samadhi lies at its foundation. According to the Platform Sutra, contemplation-samadhi is one body with two parts. After a long period of samadhi, the function of contemplation occurs, and after a long period of contemplation, the function of samadhi manifests. When we begin the practice of samadhi-contemplation, most probably we begin with a scattered mind, which is not yet settled, and is crowded with illusory thoughts. At this time, we need to practice a method of samatha to settle the mind. For example, we might select from among body and mind relaxation, experiencing the breath, or counting the breath. In the beginning all of these are methods of samadhi cultivation.

What is samadhi cultivation? It is precisely allowing the mind to arise with the function of calmness and stableness. One must practice samadhi continuously without stopping. When illusory thoughts arise, quickly go back to the method. If the method is counting the breaths, then quickly go back to that method. Practice this way until you have very few or no illusory thoughts. At this point you may start cultivating contemplation.

What is samadhi cultivation? It is precisely allowing the mind to arise with the function of calmness and stableness. One must practice samadhi continuously without stopping. When illusory thoughts arise, quickly go back to the method. If the method is counting the breaths, then quickly go back to that method. Practice this way until you have very few or no illusory thoughts. At this point you may start cultivating contemplation.

Contemplation means using your mind to observe feelings and thoughts that arise from your body and mind. Only observe them, know they occur, don't react to them, interfere or prevent them from happening. It's like watching a basketball game. You can't just jump onto the court to interfere with the players. Let the players play their own game; you just quietly enjoy it. The sensations and thoughts in your body and mind are like the players on the court. You enjoy watching them; you don't pay special attention to one particular player; rather, you watch the game in its entirety.

If your mind becomes scattered again after a long period of contemplation, return to samadhi cultivation. If you were counting the breaths, then go back to that again. When the mind is settled, begin to cultivate contemplation.

If you know how to cultivate contemplation, continue to the next step of contemplating the total body. By "total body," we mean the totality of one's physical body, one's sensations, one's breath, and one's mind (thoughts and feelings). So here, when we refer to the total body, we mean to include all these things. Contemplating the total body in the sense defined here is the practice of Silent Illumination Chan, and it is precisely the key and foundation for cultivating the mind of non-abiding. On the basis of the mind of nonabiding, Master Sheng Yen speaks of Silent Illumination Chan as having six stages: (1) relaxing body and mind, (2) experiencing the breath, (3) contemplating the total body, (4) contemplating the environment as a whole, (5) direct contemplation, and (6) contemplating emptiness.

If you know how to cultivate contemplation, continue to the next step of contemplating the total body. By "total body," we mean the totality of one's physical body, one's sensations, one's breath, and one's mind (thoughts and feelings). So here, when we refer to the total body, we mean to include all these things. Contemplating the total body in the sense defined here is the practice of Silent Illumination Chan, and it is precisely the key and foundation for cultivating the mind of non-abiding. On the basis of the mind of nonabiding, Master Sheng Yen speaks of Silent Illumination Chan as having six stages: (1) relaxing body and mind, (2) experiencing the breath, (3) contemplating the total body, (4) contemplating the environment as a whole, (5) direct contemplation, and (6) contemplating emptiness.

(To be continued)

The Diamond Sutra contains the sentence, "(One) ought not abide anywhere, and there will arise this mind." Before he became the Sixth Patriarch, the young Huineng became enlightened when he heard this single sentence. In Chan, we often use a briefer phrase, "Non-abiding, mind arising." This phrase appears within the entrances to Nung Chan Monastery and the Chan Hall of Dharma Drum Mountain in Taiwan, as well as the Chan Hall of the Dharma Drum Retreat Center in the United States. Master Sheng Yen continually brought up this phrase during long retreats, explained the concepts behind it, and asked retreatants to practice accordingly.

The Diamond Sutra contains the sentence, "(One) ought not abide anywhere, and there will arise this mind." Before he became the Sixth Patriarch, the young Huineng became enlightened when he heard this single sentence. In Chan, we often use a briefer phrase, "Non-abiding, mind arising." This phrase appears within the entrances to Nung Chan Monastery and the Chan Hall of Dharma Drum Mountain in Taiwan, as well as the Chan Hall of the Dharma Drum Retreat Center in the United States. Master Sheng Yen continually brought up this phrase during long retreats, explained the concepts behind it, and asked retreatants to practice accordingly.The Chan school places great importance on "non-abiding, mind arising" because the intrinsic nature of the mind is exactly non-abiding. If you wish to be enlightened, your actions must be in accordance with "non-abiding, mind arising." Not only must you have a clear sense of this idea, but your every action, word, and thought must be in line with it. This idea that all actions of body, speech, and mind should be in accord with the concept of non-abiding is expressed in the saying by the Huineng: "As the mouth speaks, so the mind acts."

There are many places in the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch that refer to how one should practice non-abiding. For example, the chapter "Samadhi and Wisdom Are One" says that those who practice non-abiding will see the emptiness inherent in virtue and evil, beauty and ugliness, enemy and friend, demeaning and argumentative language. Such a person does not engage in or think about reward or injury. Thought after thought, he or she doesn't engage in or think about the previous condition. If the previous thought, present thought and future thought continue without stopping, this is called "bondage." If, in regard to all dharmas, thought after thought continues with non-abiding, this is called "unbinding."

Obviously, on an intellectual level, at the outset one knows that all worldly ideas of virtue, evil, beauty and ugliness are empty, impermanent and without self. Our enemies as well as those close to us are empty, impermanent and without self. The deceptions and difficulties that others give to us through words and arguments are also empty, impermanent andwithout self. We should not be ready to seek revenge or argue and offer explanations. In applying this principle, when we are present in each moment, thought after thought, we do not react, make distinctions, or grasp or reject. However, when each successive thought is caught up with the previous thought and the present state (whatever your attention turns to) is encountered, then distinctions of other, self, right, wrong, good and bad, arise. This thought process then triggers the subsequent thought (which is now the present thought). And then the next thought will follow this present thought, and we again make distinctions between other, self, right, wrong, good and bad. This thought process continueswithout end. Again, this is bondage. If the mind doesn't differentiate, grasp or reject any past, present or future phenomena, then this is called "without bondage."

Obviously, on an intellectual level, at the outset one knows that all worldly ideas of virtue, evil, beauty and ugliness are empty, impermanent and without self. Our enemies as well as those close to us are empty, impermanent and without self. The deceptions and difficulties that others give to us through words and arguments are also empty, impermanent andwithout self. We should not be ready to seek revenge or argue and offer explanations. In applying this principle, when we are present in each moment, thought after thought, we do not react, make distinctions, or grasp or reject. However, when each successive thought is caught up with the previous thought and the present state (whatever your attention turns to) is encountered, then distinctions of other, self, right, wrong, good and bad, arise. This thought process then triggers the subsequent thought (which is now the present thought). And then the next thought will follow this present thought, and we again make distinctions between other, self, right, wrong, good and bad. This thought process continueswithout end. Again, this is bondage. If the mind doesn't differentiate, grasp or reject any past, present or future phenomena, then this is called "without bondage."How then do we not differentiate, grasp or reject phenomena of the past, present and future? We need to cultivate samatha (samadhi) and vipassana (contemplation), or, if one practices Chan, Silent Illumination or Huatou. These contemplation methods lead to the state of non-differentiation—neither grasping nor rejecting past, present or future phenomena. However, the mind can only achieve this effect when samadhi lies at its foundation. According to the Platform Sutra, contemplation-samadhi is one body with two parts. After a long period of samadhi, the function of contemplation occurs, and after a long period of contemplation, the function of samadhi manifests. When we begin the practice of samadhi-contemplation, most probably we begin with a scattered mind, which is not yet settled, and is crowded with illusory thoughts. At this time, we need to practice a method of samatha to settle the mind. For example, we might select from among body and mind relaxation, experiencing the breath, or counting the breath. In the beginning all of these are methods of samadhi cultivation.

What is samadhi cultivation? It is precisely allowing the mind to arise with the function of calmness and stableness. One must practice samadhi continuously without stopping. When illusory thoughts arise, quickly go back to the method. If the method is counting the breaths, then quickly go back to that method. Practice this way until you have very few or no illusory thoughts. At this point you may start cultivating contemplation.

What is samadhi cultivation? It is precisely allowing the mind to arise with the function of calmness and stableness. One must practice samadhi continuously without stopping. When illusory thoughts arise, quickly go back to the method. If the method is counting the breaths, then quickly go back to that method. Practice this way until you have very few or no illusory thoughts. At this point you may start cultivating contemplation.Contemplation means using your mind to observe feelings and thoughts that arise from your body and mind. Only observe them, know they occur, don't react to them, interfere or prevent them from happening. It's like watching a basketball game. You can't just jump onto the court to interfere with the players. Let the players play their own game; you just quietly enjoy it. The sensations and thoughts in your body and mind are like the players on the court. You enjoy watching them; you don't pay special attention to one particular player; rather, you watch the game in its entirety.

If your mind becomes scattered again after a long period of contemplation, return to samadhi cultivation. If you were counting the breaths, then go back to that again. When the mind is settled, begin to cultivate contemplation.

If you know how to cultivate contemplation, continue to the next step of contemplating the total body. By "total body," we mean the totality of one's physical body, one's sensations, one's breath, and one's mind (thoughts and feelings). So here, when we refer to the total body, we mean to include all these things. Contemplating the total body in the sense defined here is the practice of Silent Illumination Chan, and it is precisely the key and foundation for cultivating the mind of non-abiding. On the basis of the mind of nonabiding, Master Sheng Yen speaks of Silent Illumination Chan as having six stages: (1) relaxing body and mind, (2) experiencing the breath, (3) contemplating the total body, (4) contemplating the environment as a whole, (5) direct contemplation, and (6) contemplating emptiness.

If you know how to cultivate contemplation, continue to the next step of contemplating the total body. By "total body," we mean the totality of one's physical body, one's sensations, one's breath, and one's mind (thoughts and feelings). So here, when we refer to the total body, we mean to include all these things. Contemplating the total body in the sense defined here is the practice of Silent Illumination Chan, and it is precisely the key and foundation for cultivating the mind of non-abiding. On the basis of the mind of nonabiding, Master Sheng Yen speaks of Silent Illumination Chan as having six stages: (1) relaxing body and mind, (2) experiencing the breath, (3) contemplating the total body, (4) contemplating the environment as a whole, (5) direct contemplation, and (6) contemplating emptiness.(To be continued)